|

Cannabis Hemp Engraving

F P Nodder, May 1788 |

One

of the most common misunderstandings about cannabis and hemp is that

cannabis is the female and hemp is the male of the plant; in fact,

nothing could be further from the truth. A

simple botany lesson shows the botanical name of a plant consists of

'Botanical

Latin'

words, denoting a generic name (the genus) and the specific epithet

(the species, usually two words, but can be three).

Cannabis

sativa L., is a member of the Cannabaceae

family. Cannabis

is the plant genus, sativa

(Latin for 'cultivated') is the species (and is included in many

plant species names, e.g., rice is Oryza sativa L.), and the 'L.'

(not always used) denotes the authority who first named the species,

Carolus (Carl) Linnaeus, the Swiss botanist considered the 'Father of

Taxonomy'.

Cannabis

sativa L., is;

an

annual,

herbaceous

- denoting or relating to herbs (in the botanical sense),

usually

dioecious - either exclusively male or exclusively female,

or

monoecious - having the stamen (male, pollen-containing anther and

filament) and the pistil (female, ovule-bearing) in the same plant

(hermaphrodite).

Thus,

as the Help End Marijuana Prohibition (HEMP) Party of Australia so

rightly point out, cannabis is a herb.

A

high-resin crop, cannabis is generally planted about 1.2-1.5m (four

to five feet) apart and mostly used for its medicinal/therapeutic

leaves and buds. Hemp is a low-resin crop, generally planted about 10

cm (four inches) apart, mostly used for its versatile stalk and seed.

Different types of cannabis are classified as strains and different

kinds of hemp are classified as varieties and cultivars.

A

high-resin crop, cannabis is generally planted about 1.2-1.5m (four

to five feet) apart and mostly used for its medicinal/therapeutic

leaves and buds. Hemp is a low-resin crop, generally planted about 10

cm (four inches) apart, mostly used for its versatile stalk and seed.

Different types of cannabis are classified as strains and different

kinds of hemp are classified as varieties and cultivars.

Hemp

was, for medieval Europeans, a generic term used to describe any

fibre. With European expansion, fibre plants encountered during

exploration were commonly called 'hemp'. Thus there is a bewildering

variety of plants carrying the name hemp, including; Manila hemp

(abacá, Musa textilis), Sisal hemp (Agave sisalana), New Zealand

hemp/flax (Phormium tenax), Brown/Madras/Sunn hemp (Crotalaria

juncea), Indian hemp (jute, Corchorus capsularis or C. clitorus) and

Indian hemp (Apocynum cannabinum).

|

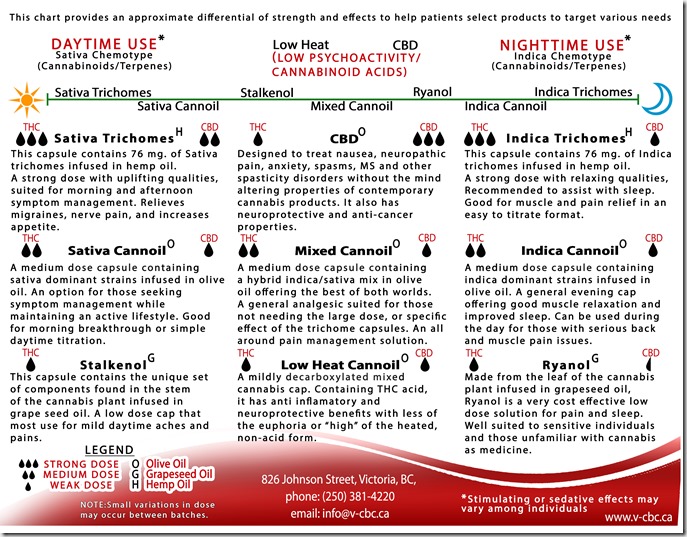

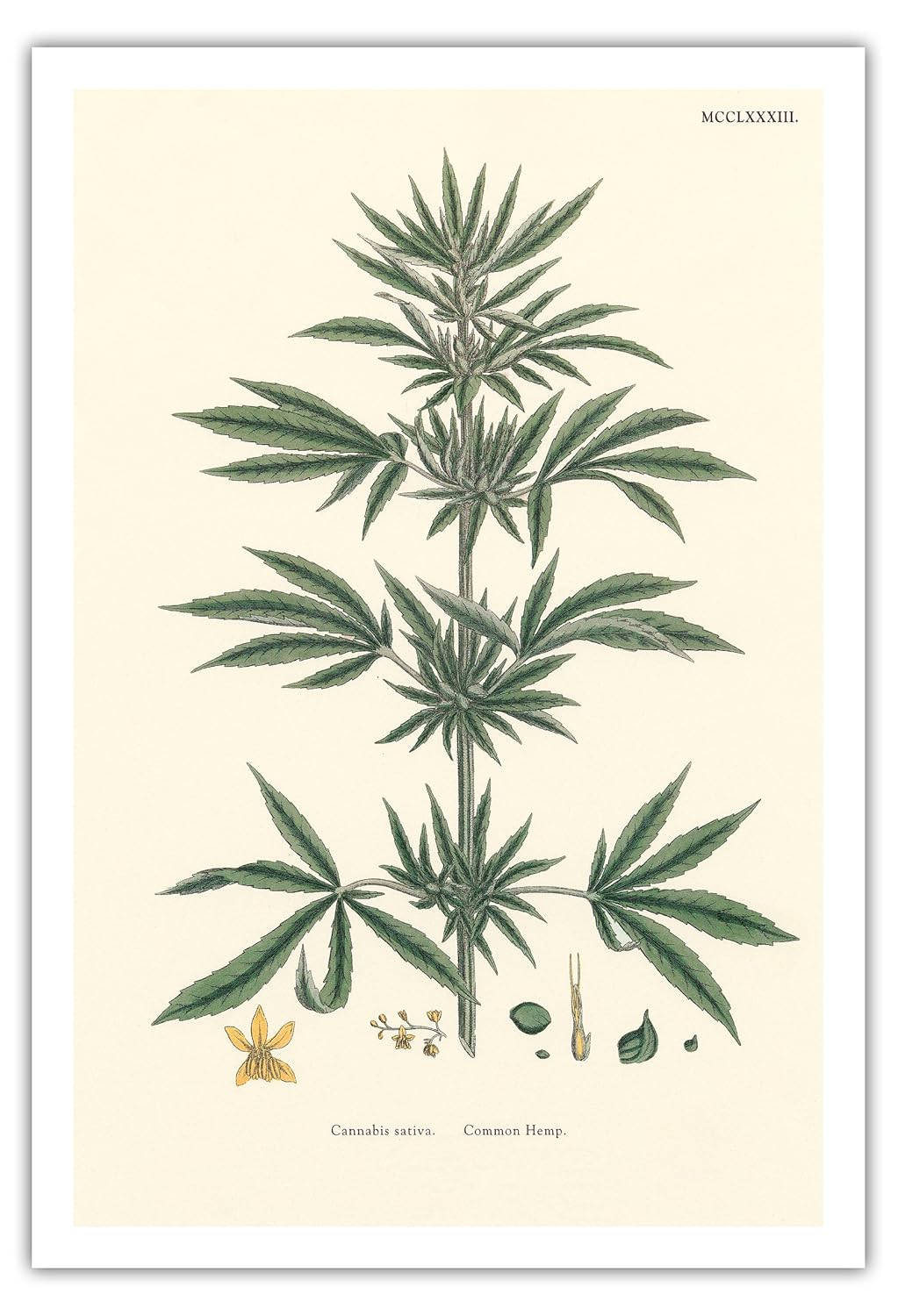

Cannabis Sativa Botanical Illustration

John Sowerby 1883 |

The

botanical confusion was compounded by the introduction of one word,

'marihuana' (now commonly 'marijuana'). The word was first coined in

the 1894 Scribner's Magazine feature "The American Congo"

by John G. Bourke. Bourke was describing the native flora that

flourished on the banks of the Rio Grande River that forms the border

between the US state of Texas and Mexico. The term was adopted by the

United States Bureau of Narcotics in the 1930's to describe all forms

of Cannabis sativa L., and to this day, North Americans, in

particular, continue to call the plant 'marijuana' without regard to

botanical distinctions.

The

international definition of hemp was developed by a Canadian

researcher, Ernest Small, in 1971. His arbitrary 0.3% THC limit

became standard around the world as the official limit for 'legal'

hemp, after he published a little-known, but very influential book,

The Species Problem in Cannabis.

In his book, Small discussed how “there

is not any natural point at which the cannabinoid content can be used

to distinguish strains of hemp and marijuana,” despite

this he continued to “draw

an arbitrary line on the continuum of cannabis types and decided that

0.3% THC in a sifted batch of cannabis flowers was the difference

between hemp and marijuana” and

this continues to add to the controversy and confusion as to what

truly constitutes the difference between cannabis and hemp.

Hemp

is an agricultural commodity that is cultivated for use in the

production of a wide range of products including; foods and

beverages, cosmetics, personal care products, nutritional

supplements, fabrics and textiles, yarns and spun fibres, paper,

construction and insulation materials, and other manufactured goods.

Hemp can be grown as a fibre, seed, or other dual-purpose crop. In

2015, some estimate that the global market for hemp consists of more

than 25,000 products.

Popular

Mechanics dubbed hemp “the new billion dollar crop” in

1938, claiming that it “can be used to produce more than 25,000

products, ranging from dynamite to cellophane.” And when World War

II demanded the full industrial might of the US, hemp restrictions

were temporarily lifted and production reached its peak in 1943 when

American farmers grew 150 million pounds of hemp. It was manufactured

into shoes, ropes, fire hoses and even parachute webbing for soldiers

fighting the war. After 1943, production plummeted and the

anti-narcotic regime kicked back into effect.

Hemp

seed oil is valued primarily for its nutritional properties as well

as for the health benefits associated with it. Although its fatty

acid composition is most often noted, with oil content ranging from

25-35%, whole hemp seed is additionally comprised of approximately

20-25% protein, 20-30% carbohydrates, and 10-15% fibre, along with

trace minerals. A complete source of all essential amino and fatty

acids, hemp seed oil is a complete nutritional source. In addition,

constituents exist within the oil that have been shown to exhibit

pharmacological activity.

In Australia, due to the current outdated and draconian laws (and ignorance on behalf of law enforcement in particular), it is illegal to

consume hemp products unless you are an animal. Australians can,

however, use hemp products topically. Food Standards Australia New

Zealand (FSANZ) state on their website;

Hemp

or industrial hemp is a Cannabis plant species (Cannabis sativa).

Historically, hemp has been used as a source of fibre and oil.

Cannabis extracts have also been used in medicine for a variety of

ailments. Hemp is different to other varieties of Cannabis sativa,

commonly referred to as marijuana. Hemp contains no, or very low

levels of THC (delta 9-tetrahydrocannabinol), the chemical associated

with the psychoactive properties of marijuana. Hemp is cultivated

worldwide, including in Australia and New Zealand (under strict

licensing arrangements) and is currently used in Australia as a

source of clothing and building products. Hemp seeds contain protein,

vitamins and minerals and polyunsaturated fatty acids, particularly

omega-3 fatty acids. Hemp seed food products may provide an

alternative dietary source of these nutrients. At present, hemp

cannot be used in food in Australia and New Zealand as it is

prohibited in the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code. However,

hemp oil has been permitted in NZ since 2002 under the New

Zealand Food (Safety) Regulations.

Hemp

is used in other countries, including in Europe, Canada and the

United States, in a range of foods including health bars, salad oils,

non-soy tofu, non-dairy cheeses and as an additive to baked goods. It

can also be used as the whole seed, raw or roasted.

But this was the answer to the question of re-legalising hemp for human consumption (January 2015);

Review of Low THC Hemp as a Food. Application 1039 – low tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) hemp as a food. The Forum in December 2012 requested FSANZ review its decision. FSANZ has reviewed its decision and re-affirmed its support of variation to the Code. The Forum noted FSANZ found foods derived from seeds of low THC hemp do not present any safety concerns as food and concerns regarding the impact on police THC drug testing fall beyond the remit of FSANZ. The Forum resolved to reject the proposed variation to Standard 1.4.4 (Prohibited and Restricted Plants and Fungi) resulting from Application A1039. Several concerns were raised by Forum Members, including law enforcement issues, particularly from a policing perspective in relation to roadside drug testing, cannabidiol levels as well as the marketing of hemp in food may send a confused message to consumers about the acceptability and safety of cannabis. The Forum agreed further work would be undertaken promptly to consider law enforcement, roadside drug testing and marketing concerns in consultation with relevant Ministers.

Law enforcement is the main reason hemp is not available legally as a food source in both Australia and New Zealand and we are the only two countries in the entire world where this idiocy is so.

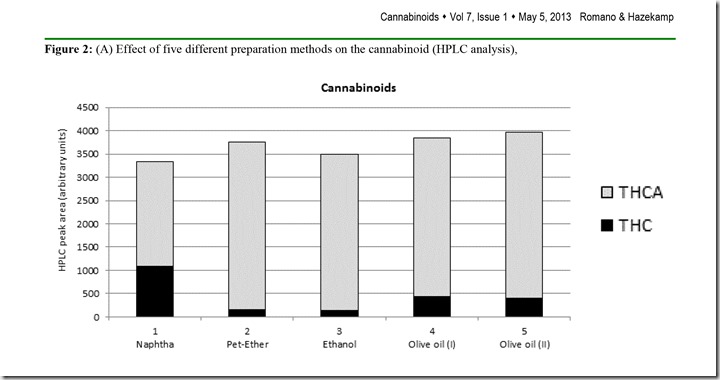

|

Cannabis Sativa Botanical Illustration

|

The

strict laws surrounding both cannabis and hemp have made research

very difficult. Of the thousands of academic and research bodies in

the US and Canada alone, whom would be equipped to perform

agricultural or medical research on this unique species, only around

40 had actual research licenses to study the plant in a limited

context. Despite these barriers, researchers have made progress in

understanding the way cannabis works medicinally and therapeutically

to assist in managing an ever-expanding list of disorders. What’s

more, developments in hemp technology continue to reveal new and

intriguing ways that this plant can contribute to society in the

future. In 2014, researchers at the University of Alberta created a

supercapacitor

using

raw hemp material, making the manufacturing of cheap, fast-charging

batteries from hemp a real possibility. Hemp fibre is also being used

to develop

new

forms of renewable plastic, which has made it a common material in

the car parts industry.

But

as re-legalisation spreads across the globe, the opportunities to

explore the potential of cannabis grows too. The possibilities are

endless, and that is one thing cannabis and hemp have in common.

Resources include: