Dr Tod Mikuriya (1935-2007), a former Berkeley, California, United States (US) Psychiatrist, may be unknown by many new to the movement to re-legalise cannabis (worldwide) and Tod himself would not have been surprised about his leadership role being obscured. “It’s not just marijuana* that got prohibited, it’s the truth about history”, he used to say.

In 1959 during his second year of medical school he read a book on pharmacology which chronicled early American uses of cannabis oils and tinctures. By the end of the summer he had also read everything on cannabis available in the school’s medical library and had travelled to Mexico to sample the plant. Upon graduating he found work with Humphrey Osmond in research at the New Jersey Psychiatric Institution at Princeton; Mikuriya was hired as Director of its Drug Abuse Treatment Centre. Osmond, credited with coining the term ‘psychedelic’, introduced Mikuriya to Timothy Leary, America’s leading light on all things LSD and to members of the San Francisco Diggers, informal anarchists with a passion for guerilla theatre. During his months off he travelled to Morocco and Nepal where he befriended locals and observed the cultivation and use of cannabis.

In 1967 Dr Mikuriya was recruited as Director of non-classified marijuana research for the US National Institute for Mental Health. The ‘non-classified’ designation is important, as from 1945-1975 there was much classified research on 'marihuana' carried out both by the CIA in its MK-Ultra program and by the US Army. It did not take Mikuriya long to discover NIMH’s anti-cannabis bias. When the Institute sent him out to spy on San Francisco communes he arrived, checked out the culture, found it congenial and stayed on.

Dr Mikuriya was not only an MD he was also an historian, publishing an anthology of the pre-prohibition literature entitled, Volume One Marijuana: Medical Papers, 1839-1972, which unearthed the western history of medical cannabis (there are two other volumes: Volume Two: Clinical Studies and Volume Three: Collected Works of Tod Mikuriya, MD, you can find all these online). The Medical Papers introduced North Americans of the day to the 19th Century published works of Dr William O’Shaughnessy, as well as to the works of other doctors influenced by him. O’Shaughnessy served as surgeon and physician for the British East India Company in Calcutta from 1833-1842. He was a quick study in languages and whilst there travelled widely, immersing himself in studies with local Ayurvedic doctors, who routinely employed what he called 'Indian Hemp'. He learned to develop his own tinctures and conducted experiments on animals and humans. He returned to England with plant specimens for the Royal Horticultural Society and quantities of prepared Indian Hemp (cannabis) medicine to share with European and North American doctors. Thanks to O’Shaughnessy’s many lectures and publications, news of medical cannabis spread throughout Canada and the US. Thanks to his careful documentation, local doctors and chemists were able produce their own potent tinctures and to use them as they and their patients saw fit.

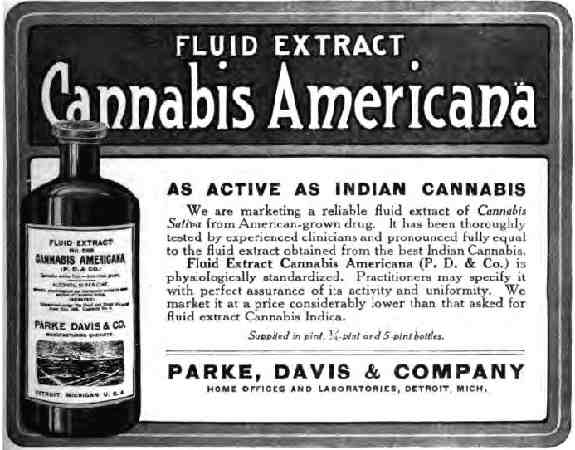

Pharmaceutical companies followed suit, pouring medicines into those now collectible bottles whose images we love to post. Cannabis tincture or oil became standard over the counter remedies until the early 1940's, when they were forcibly removed from the formularies - though not before over a 100 clinical studies on these remedies had been published in the medical journals of the day. These were the studies that Mikuriya had discovered and had made available to a 1970's public that had lost all memory of them.

Dr Mikuriya helped draft Proposition 215, the 1996 initiative that legalised cannabis for medical use in California, US. He insisted the law should cover not just the gravely ill, but patients coping with “any other condition for which marijuana* provides relief”. For several years after Prop., 215 passed, Tod was the only doctor in California known to issue approvals readily for conditions other than AIDS and cancer. He called the new law “a unique research opportunity”, and kept adding to the list of conditions known to be treatable by cannabis.

In 1959 during his second year of medical school he read a book on pharmacology which chronicled early American uses of cannabis oils and tinctures. By the end of the summer he had also read everything on cannabis available in the school’s medical library and had travelled to Mexico to sample the plant. Upon graduating he found work with Humphrey Osmond in research at the New Jersey Psychiatric Institution at Princeton; Mikuriya was hired as Director of its Drug Abuse Treatment Centre. Osmond, credited with coining the term ‘psychedelic’, introduced Mikuriya to Timothy Leary, America’s leading light on all things LSD and to members of the San Francisco Diggers, informal anarchists with a passion for guerilla theatre. During his months off he travelled to Morocco and Nepal where he befriended locals and observed the cultivation and use of cannabis.

In 1967 Dr Mikuriya was recruited as Director of non-classified marijuana research for the US National Institute for Mental Health. The ‘non-classified’ designation is important, as from 1945-1975 there was much classified research on 'marihuana' carried out both by the CIA in its MK-Ultra program and by the US Army. It did not take Mikuriya long to discover NIMH’s anti-cannabis bias. When the Institute sent him out to spy on San Francisco communes he arrived, checked out the culture, found it congenial and stayed on.

Dr Mikuriya was not only an MD he was also an historian, publishing an anthology of the pre-prohibition literature entitled, Volume One Marijuana: Medical Papers, 1839-1972, which unearthed the western history of medical cannabis (there are two other volumes: Volume Two: Clinical Studies and Volume Three: Collected Works of Tod Mikuriya, MD, you can find all these online). The Medical Papers introduced North Americans of the day to the 19th Century published works of Dr William O’Shaughnessy, as well as to the works of other doctors influenced by him. O’Shaughnessy served as surgeon and physician for the British East India Company in Calcutta from 1833-1842. He was a quick study in languages and whilst there travelled widely, immersing himself in studies with local Ayurvedic doctors, who routinely employed what he called 'Indian Hemp'. He learned to develop his own tinctures and conducted experiments on animals and humans. He returned to England with plant specimens for the Royal Horticultural Society and quantities of prepared Indian Hemp (cannabis) medicine to share with European and North American doctors. Thanks to O’Shaughnessy’s many lectures and publications, news of medical cannabis spread throughout Canada and the US. Thanks to his careful documentation, local doctors and chemists were able produce their own potent tinctures and to use them as they and their patients saw fit.

Pharmaceutical companies followed suit, pouring medicines into those now collectible bottles whose images we love to post. Cannabis tincture or oil became standard over the counter remedies until the early 1940's, when they were forcibly removed from the formularies - though not before over a 100 clinical studies on these remedies had been published in the medical journals of the day. These were the studies that Mikuriya had discovered and had made available to a 1970's public that had lost all memory of them.

Dr Mikuriya helped draft Proposition 215, the 1996 initiative that legalised cannabis for medical use in California, US. He insisted the law should cover not just the gravely ill, but patients coping with “any other condition for which marijuana* provides relief”. For several years after Prop., 215 passed, Tod was the only doctor in California known to issue approvals readily for conditions other than AIDS and cancer. He called the new law “a unique research opportunity”, and kept adding to the list of conditions known to be treatable by cannabis.

In 2000 Dr Mikuriya founded a group called the California Cannabis Research Medical Group (now the Society of Cannabis Clinicians) so that doctors issuing approvals could share their experiences, clinical and legal. He foresaw that Cannabis Therapeutics would emerge as a specialty in its own right, and that a journal was needed so that doctors in the field would have an outlet to publish their findings and observations. Publishing Cannabis as a Substitute for Alcohol: A Harm Reduction Approach, was a big part of the motivation in launching O’Shaughnessy’s in 2003.

'Harm reduction' is a treatment approach that seeks to minimise the occurrence of drug/alcohol addiction and its impacts on the addict/alcoholic and society at large. A harm-reduction approach to alcoholism adopted by 92 of Dr Mikuriya's patients in northern California involved the substitution of cannabis - with its relatively benign side-effect profile - as their intoxicant of choice. No clinical trials of the efficacy of cannabis as a substitute for alcohol were reported in the then literature and there were no papers directly on point prior to Dr Mikuriya's own account (1970) of a patient who used cannabis consciously and successfully to reduce her problematic drinking.

In the late 19th century in the US, cannabis was listed as a treatment for delirium tremens in standard medical texts (Edes 1887, Potter 1895) and manuals (Lilly 1898, Merck 1899, Parke Davis 1909). Since delirium tremens signifies advanced alcoholism, we can adduce that patients who were prescribed cannabis and used it on a long-term basis were making a successful substitution. By 1941, due to prohibition, cannabis was no longer a treatment option, but attempts to identify and synthesise its active ingredients continued.

In the late 19th century in the US, cannabis was listed as a treatment for delirium tremens in standard medical texts (Edes 1887, Potter 1895) and manuals (Lilly 1898, Merck 1899, Parke Davis 1909). Since delirium tremens signifies advanced alcoholism, we can adduce that patients who were prescribed cannabis and used it on a long-term basis were making a successful substitution. By 1941, due to prohibition, cannabis was no longer a treatment option, but attempts to identify and synthesise its active ingredients continued. A synthetic Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) called pyrahexyl was made available to clinical researchers and one paper from the postwar period reports its successful use in easing the withdrawal symptoms of 59 out of 70 alcoholics (Thompson and Proctor 1953). In 1970 Dr Mikuriya reported on Mrs A., a 49-year-old female patient whose drinking had become problematic. The patient had observed when she smoked cannabis socially on weekends, she decreased her alcoholic intake. She was instructed to substitute cannabis any time she felt the urge to drink. This regimen helped her to reduce her alcohol intake to zero. The paper concluded, “It would appear that for selected alcoholics the substitution of smoked cannabis for alcohol may be of marked rehabilitative value. Certainly cannabis is not a panacea, but it warrants further clinical trial in selected cases of alcoholism”. The warranted research could not be carried out under conditions of prohibition, but in private practice and communications with colleagues Dr Mikuriya encountered more patients like Mrs A. and generalised that somewhere in the experience of certain alcoholics, cannabis use is discovered to overcome pain and depression - target conditions for which alcohol is originally used - but without the disinhibited emotions or the physiologic damage.

By substituting cannabis for alcohol, they can reduce the harm their intoxication causes themselves and others. Although the increasing use of cannabis starting in the late 1960's had renewed interest in its medical properties - including possible use as an alternative to alcohol, meaningful research was blocked until the 1990's, when the establishment of “buyers clubs” in California created a potential database of patients who were using cannabis to treat a wide range of conditions. The medical cannabis initiative passed by voters in 1996 mandated prospective patients get a doctor’s approval in order to treat a given condition with cannabis - resulting in an estimated 30,000 physician approvals as of May 2002.

A 2009 study published in the Harm Reduction Journal, Cannabis as a Substitute for Alcohol, came to the conclusion that the substitution of one psychoactive substance for another with the goal of reducing negative outcomes can be included within the framework of 'harm reduction' and that medical cannabis patients have been engaging in substitution by using cannabis as an alternative to alcohol, prescription and illicit drugs. "Substitution can be operationalised as the conscious choice to use one 'drug' (legal or illicit) instead of, or in conjunction with, another due to issues such as: perceived safety; level of addiction potential; effectiveness in relieving symptoms; access and level of acceptance. This practice of substitution has been observed among individuals using cannabis for medical purposes. This study examined drug and alcohol use and the occurrence of substitution among medical cannabis patients.

Successful use of cannabis as a less harmful substitute for alcohol and other toxic substances continues with statistics out of Canada, from the University of Victoria, showing reasons cited for using cannabis by Canadian patients instead of other substances, including better symptom management and less adverse side effects.

|

| 2015 Statistics out of Canada from the University of Victoria |

Adapted from How Cannabis Acts as a Substitute for Alcohol and a Cure for Alcoholism and Medical Cannabis in Perspective Remembering Tod Mikuriya, Cannabis as a substitute for alcohol and other drugs

No comments:

Post a Comment